Thoughts and Encouragements for Wounded Helpers

Joined to a Healing God |

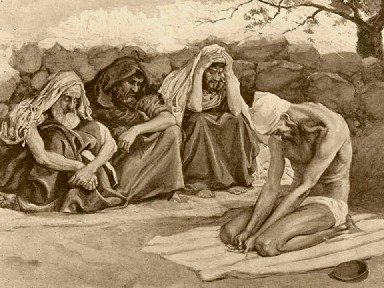

Modernism and the Friends of Job |

At the time I wrote the original Dutch version of this

article, in March 2004, I had just heard a sermon on the radio about the

advises that Job got from his friends when he was in deep trouble.1 I considered that a

superb illustration of something I had already wanted to write about for a

long time.

That ‘something’ is modernism and post-modernism. But before I

dig into that, let me first discuss what happened between Job and his

friends.

What is the situation? The adversary of God complains

towards God. That is his nature. To complain and to accuse. About Job he

says something like: “Yes, no wonder that he serves You, You make it

very easy and comfortable: a fine family, a nice house, and in any other

material way all that he could long for! No wonder he is content! But when

some of those things would be taken from him, I bet he will surely leave

You!”

God accepts the challenge, for He knows the nature of the heart of Job.

God knows that Job is not going to forsake Him. The result is that the

adversary takes everything from him, bit by bit. Finally Job is sitting

under the open sky, his family dead, his house destroyed, his health

severely deteriorated.

He then complains towards God – he feels it is not fair, all that

happened to him.

|

And I recognize a lot in that. For, wouldn’t we all love the world around us to be explainable in simple terms? And, when we are facing a troublesome situation, don’t we all wish that we can easily reach a conclusion on what to do about it?

But, was the situation indeed as described by

Eliphaz’ simple theology? From the background described in the first

chapters of the book of Job, we know better. There were things going on of

which neither Job, nor Eliphaz, nor one of Job’s other friends had any

idea or suspicion.

That was the cause that the ‘big truths’ (‘God is

love’, ‘God is righteous and does not punish without

reason’, etc.) carried on by Eliphaz became rather cheap and not

applicable.

Oh, certainly, each on its own, and apart from the situation, these

assertions were ‘right’...

Each assertion in itself was ‘true’.

But ‘the truth’, in the sense of: giving a good and clear view

on the situation of Job, they did not present at all.

As it appears at the end of the story, God isn’t so fond of this kind

of cheap way of lacing assertions or ‘truths’ (cf. Job 42:7-10).

He then says: „you did not speak rightly of Me, as my servant Job

has.”

The truth is not a simple collection of theological ‘rules’

that we can hold in our hands and apply simply.

The Truth is a Person! (cf. John 14:6) He is far beyond our

comprehension! That is Job’s conclusion also, in Chapter 42, when God

has confronted him with Who He is: “I know that You can do all things,

and that no purpose of Yours can be thwarted. ‘Who is this that hides

counsel without knowledge?’ Therefore I have uttered what I did not

understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know. ‘Hear,

and I will speak; I will question You, and You declare to me.’ I had

heard of You by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees You; therefore

I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes.” (Job 42: 1-5).

Then Job understood, that his words had been too big for a simple creature

towards the Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth.

Now to modernism and postmodernism. Is the above not a great illustration of what I sometimes call: ‘the bankruptcy of modernism’?

Once upon a time, far from here, there was a land that was reigned by a good king. This king was very wise and good, such that all who listened to Him reaped the good and sweet fruits of that, and the land knew much peace. Certainly, there were also people who did not like this king and went their own way, but yet the influence of this good king was noticeable in the entire social life. In a particular era, among a group of intellectuals -

soon they were named ‘the know-it-alls’ - more and more

resistance against this king arose. You know, it was such that He found

everyone important, not just them, as intellectuals, especially.

These people wanted more influence. They wanted to be kings themselves.

Thus it happened that they undermined the kingship of the good king

more and more, until they in fact had undermined the complete social life

of the land and in everything their influence was noticeable. With the aid

of foreign armies they had committed a coup d’etat, declaring the

old king dead. They had done this in such a way that the insecurity of many

‘ordinary’ people urged those to pay no attention to the king

anymore and only listen to this group of ‘the know-it-alls’.

Wherever they could, they undermined every thought of the good king and

of the time when people still granted him so much influence and many were

happy. The consequence was, that life in the land deteriorated in many

aspects, more and more. O, certainly, ‘the know-it-alls’ had

cared also - at least they had it appear this way - that many people

had started to attach more value to material wealth. And indeed many had

gathered more riches. (In reality this greater wealth had been caused less

by the know-it-alls than by a group renewers who had been there before the

know-it-alls and who had called the people to follow the good king, but

that as an aside.) |

Let me elaborate and explain a bit of the background

against which modernism arose. To begin with, it was founded on Greek

thinking. It arose in reaction to a morbid growth of emotionally laden

superstition, and was fertilized by the secularisation (leaving God) that

started with Thomas of Aquino and culminated in the French revolution, the

so called ‘renaissance’, the ‘enlightenment’ and the

‘God-is-dead’ -theory. This was the background of the modernism

that has been so decisive for the developments in western culture of the

nineteenth and twentieth century. What comes forward strongly in modernism,

is the urge of man to control everything by his own mind and apart from God

(cf. Descartes’ ‘Cogito ergo sum’ - ‘I think,

so I am’2).

That control requires the existence of simple explanation models, like the

‘theology’ of Eliphaz, discussed briefly above. Explanation

models and reasonings of the one-dimensional type: ‘if A then B,

and there is no more to it, so if not-B then also not-A’.

The existence of God and His acting in the situation is denied then.

We can illustrate this way of reasoning by comparison via the following

example: ‘if you walk in the rain with an umbrella, you do not get wet;

so, if someone is wet, he has not used an umbrella’ (that the

umbrella let some water through after hours of very heavy rain, or that

there were holes in it, or that by flares of strong wind the rain sometimes

came under the umbrella, or that passing cars gushed up water from the road,

all that is not considered). We also call this the reductionism,

because it reduces reality to a few (easily controllable) formulas.

This is expressed in modern psychology e.g. in a strongly mechanistic

view of man and his or her illnesses emphasizing a strongly intellectually

driven diagnosis-formation with the aid of a limited collection of

‘recognized clinical pictures’, each described from a limited

number of phenomena (and hence not so much from the causes). The role of

listening is seen as important, but is also limited because there is no

essential relationship between helping professional and the one seeking

help (think of the notion of ‘professional distance’),

or this is esteemed irrelevant or small. The helping psychologist or

psychotherapist is the ‘expert’ - he has studied many years

intensively for it (recognize the intellectual focus on the basis of Greek

thinking).

Reductionism and modernism also led to the phenomenon that our entire lives

seem to have been cut into small pieces. For every piece there are

‘specialists’. There is nobody anymore with oversight over

the connections. As said: to be able to control a situation, it must be

reduced, and made loose, isolated from its context or surroundings.

It is a kind of ‘divide and conquer’. The relationships –

of man with God, of man with him-/herself and with the fellow man and with

nature – have been lost more and more. Alienation, individualism and

loneliness are the sad result. That ‘specialists’ have come up

for anything and everything, also exerted a strong influence on our

perspective on mental health care and church life. For many centuries, the

pastor and the brother and sister in the Christian Community played a

central role in protecting mental health of the people in the full breadth

of society. Modernism and the ‘division’ mentioned, strongly

reduced the spiritual task of these people; psychotherapist, haptonomist,

psychologist, psychiatrist and a varied group of other professionals each

claim to possess ‘the truth’ at some small part of the

‘spiritual/mental’ terrain, at the exclusion of all others who

did not enjoy that same highly intellectual education. The emphasis moved

from ‘spiritual’ to ‘mental’. Modern ‘mental

health care’ focuses on the mental powers and on processes in our

brains.

In a last convulsion of the technocratic positivism they try to make

everything controllable, even in health care and mental health

care, by introducing large numbers of managers and rules. The result is

uncontrollability, the atmosphere getting cold, everything becoming inhumane,

while costs explode.

Over the last decades more and more people are

becoming aware of what I call the bankruptcy of this modernism.

Simple, reductionistic models obviously come short to really improve life

– both worldwide and in the home. In particular the relational, the spiritual and the intuitive, and thereby

enjoying and wonder have become severely undervalued.

The connection between spirit, mind, feeling and body got lost.

There is an ever-increasing exodus from God and church; and where God is

no longer thanked, worshipped and honored, people get estranged not only

from God, but also from themselves and each other (compare Romans 1).3

The consequences show: a society in which love and solidarity disappear,

conflicts do not get solved with mutual respect, and where relationships

do not seem to thrive anymore, where marriage is no longer for life, and

where children grow up in distant children care centers instead of with

their mother and father at home in a good family context with togetherness.

We discover that modernist thinking was too rational; too one-sided and

one-dimensional, too technical directed at function and not on being.

The consequence is emptiness and love getting cold. For, where I am only

appreciated for my performance and not for who and what I am, there I

cannot be essentially ‘home’; there everything becomes cold.

Postmodernism is the natural reaction to this.

The name already denotes it: it is not something new, but something that

follows after modernism. Thereby it is a bit as the reaction of an -often

justified- revolting adolescent, who observes the shortcomings of the

system of his parents and says: “so this is not the way!”

For example: ‘authority and power of those who claimed to have

knowledge (‘THE truth’), played a strange role in modernism,

so we don’t want any authority and power anymore, and certainly no

people who claim to have the truth!’ Or: ‘in modern reductionism,

connections were neglected, so we should strive more for a holistic vision

(i.e. a vision that does right to the connections that are there, e.g.

between health on the spiritual, bodily, mental, intuitive and emotional

plane)’. Often in these cases I can agree with the critiques of the

postmoderns. However, it is a pity that they - just like the adolescent -

often go too far, and thus remain locked in the same antithesis, and thus

in the same system. A healthy, mature lifestyle and philosophy is

characterized by not just being a reaction to something else, but be able

to form an opinion of its own, feel one’s own emotions and live by

oneself and - above all - acknowledge and honor God, Who created us.

Here and there I happily see the emergence of such more mature forms,

as in social constructionism (/constructivism) and the influence of

those on psychology, psychotherapy and pastoral care. And I have regard

for postmoderns who grow beyond the reaction of the adolescent and e.g.

dare to give relationships a more central place, in a way that looks much

like how the Bible puts relationships in the center. An example of this I

consider narrative therapy, as taught by such scholars as David Epston

and Michael White. In an article on listening I pay more attention to

that (see ‘Listening to

Multithreaded Life Stories’).

| „ ... the whole debate between the modern and

postmodern world views is a great example of a false dichotomy, which is

another way of distorting the truth, since neither view is able to explain

the meaning of life or establish the criteria for finding God.” David Takle The Truth About Lies And Lies About Truth - A fresh new look at the cunning of Evil and the means for our Transformation, Shepherd's House, Pasadena CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 0 9674357 9 4, p.10. |

Above I already spoke briefly about the shortcomings of the postmodern view (such as: not allowing a purely rational authority anymore). Often I met Christians and others who had difficulty with this because they felt at home in rational thought, not in feelings or intuition. Therefore, they opposed postmodernism fiercely.4 Personally, I often do not agree with them. Many of the shortcomings of the postmodern view actually are no more than logical reactions to shortcomings of modernism. To take again that example of authority and truth: in a deeply Christian view the truth notion plays an important role (e.g. the truth of God’s existence), but also humman modesty and humility: as fallible creatures we know truth only in part – see Job’s later words (Job 42; compare also 1 Corinthians 13:8-10). Under the influence of modernism many - even Christians - often spoke too big words where ‘the truth’ was involved, and they lifted ‘the truth’ above love. What followed was: broken relationships, sorrow, love getting cold, and partiality – all developments seriously hated by God. That postmodernism over-reacts to this by disliking human claims of absolute truth, is no more than an understandable and predictable reaction to this modernist pride that had such nasty consequences.5 In that sense I see a parallel between Job’s refusal of Eliphaz’ simplistic reasoning and the refusal of failing (!) ‘truths’ of modernism by postmodernists. And the remarkable thing is that in the end God had more sympathy with a grumbling Job, than an Eliphaz who with a too simplistic ‘theology’ seemed to defend God. Job’s story gives me the courage to continue with a certain measure of resistance towards reductionism and modernism. Sometimes I am gladly surprised to encounter temporal allies in that process, in some postmodern scientists.

| 1 | The sermon was by Rev. Henk

Fonteyn, chaplin at the Dutch Royal Army, and treated Job 4:1-9 and 17-21;

5:17-18. It was a broadcast in the series Job, a friend of God and man

of all times, of NCRV's Word on Sunday.

See also: Keith R. Anderson, Friendships that run deep - 7 ways to build lasting relationships, Inter Varsity Press, Downers Grove, Ill, 1997; ISBN 0 8308 1966 5. In Ch. 4 - ‘Somebody nobody knows’ Keith Anderson gives a similar analysis of the meeting of Job with his friends as I give here. He emphasizes the fact that Job’s friends did keep silent at first, but later failed in really listening to Job. | ||||||||

| 2 | See also: Antonio R.

Damasio, Descartes’ error - emotion, reason and the human brain,

Putnam / AVON Books, New York, 1994.

In this book Damasio demonstrates on the basis of neurological research, that emotions and thoughts cannot be mutually separated and that both can be recognized in the brain. Emotions are essential for taking good decisions. Hereby he very clearly disproves the old premises of Descartes and modernism. Eugen Rosenstock-Hüssy, ‘Farewell to

Descartes’, Ch.1 in: Eugen Rosenstock-Hüssy, I Am

an Impure Thinker I find it remarkable how the pure scientific observations of Damasio (and Rosenstock) coincide with the Biblical view on man. In Romans 11:33 - 12:3 Paul pinpoints that in reaction to God’s greatness and His great goodness, it is most fitting for us to surrender ourselves with our body to Him. That though stood perpendicular to the Greek philosophy of those days (en the later modernist (Cartesian) one) where the mind and the thinking was emphasized more and the body was seen as ‘lower’. Paul says that from that bodily surrender follow the renewal of thinking and life, yes, he puts the renewal of our thinking in the context of the surrendered body. Damasio says that our brains (body!) determine in the first place our emotions and how we treat them. And tht those emotions determine to a large extent our thinking and living. Thereby, he affirms the order the Bible gives us. About this, see also my article: Life Renewal – by a renewal of our mind, or...?, web-article at www.12accede.org, Jan. 2007 (NL) / Sept. 2009 (EN).

My criticism towards modernism is not new. The

renowned Abraham Kuyper said of religious modernism: Source: Lecture by Dr. Abraham Kuyper, ‘Het Modernisme -

een Fata morgana op Christelijk gebied’ (Modernism, a Fata morgana

in Christian respect; in Dutch), H. de Hoogh & Co., Amsterdam, 1871.

Further on he said, coupling religious modernism to the

general modernism already in longer existence: Source: Lectures by Dr. Abraham Kuyper, ‘Het calvinisme - I. Het calvinisme in de historie’, Höveker

& Wormser, Amsterdam / Pretoria, 1899 [English:

Abraham Kuyper, Lectures on Calvinism, The Stone Lectures, Princeton University,

1898

(was available as well at the site of the American Kuyper foundation].

Kuyper saw Calvinism as the principle in life itself that had to stand up against modernism. Now - more than a century later - I add to that: did not post-modernism demonstrate in life itself, i.e. in reality, the bankruptcy of modernism, and defeated it and declared it dead?

See also:

The fact that the overly rational modernism itself was a reaction on the strongly emotionally laden superstition of the in some respects somewhat ‘irrational’ time before it (think of witch hunts etc.!) is in my opinion briefly but well clarified at p.61-72 of Wim Rietkerk’s book (under ed. of Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker): Die ver is, is nabij – In de relatie met God komt de mens tot zijn recht (He Who is far, is close – In the relationship with God man comes to his destiny), Kok, Kampen, 2005; ISBN 90 435 1095 5. | ||||||||

| 3 |

|

||||||||

| 4 | Such over-simplified critiques I encountered

e.g. in the Dutch magazine Tijdschrift of the Centre

for Pastoral Counseling; in editions Nr. 43 en 44 (Vol. 10), where

Gene Edward Veith wrote on: ‘Postmodernisme - Geen ruimte voor de

waarheid’ (Postmodernism - no room for the truth) (deel 1: Nr. 43

p.28-31, deel 2: Nr. 44 p.42-45). A somewhat more balanced picture I encountered in some articles by Jef DeVriese in other editions of the same Tijdschrift (voor Theologie en Pastorale Counseling): ‘Modernisme, Postmodernisme en Hulpverlening’ (Modernism, Postmodernism and Counseling) (8th Vol, 4th Q 1997, Nr. 36, p. 23-30.), ‘Christelijke counseling, modernisme en postmodernisme. Deel 1: Gezag.’ (Christian counseling, modernism and postmodernism. Part 1: Authority) (Vol 11, Nr.49, p.10-14); ‘Deel 2: Waarheid.’ (Part 2: Truth) (Vol. 11, Nr.50, May-July 2001, p.4-8); See also: P. Lenaerts, ‘De invloed van postmodernisme op psychotherapie, Tijdschrift voor Familietherapie jrg.8, nr.3, p.21-39. ‘What is postmodernism and what does it have to do with therapy, anyway?’ - An interview with Lois Shawver, New Therapist, 6.

Joseph Bottum, ‘Christians

and Postmoderns’, First Things, February 1994. Rogier Bos, ‘The most Postmodern person in the Bible’, Next Wave, March 1999. | ||||||||

| 5 | Concerning the notion of truth in postmodernism,

there is a lot of polarisation going on. At Postmodern Therapies

NEWS, the website of Lois Sawver, an advocate of postmodernism, I read

that someone had posed a question about this notion of truth. This was

illustrated with the example of the moonlanding. Postmodern man does not

doubt the actual truth of this happening, but does say that many of the

stories about is have been and are being told from a particular point of

view; from a particular -subjective- vision, and so, they are never THE

(full, entire) truth. There is truth in those stories, but they are also

colored by the one who tells them. For me this strongly resembles the

Apostle Paul’s (non-Greek and so non-modern) observation that our

human knowing has its limits (1 Cor.13:8-10). It is not a contrast:

a story is either THE truth, or total fiction, but often it

is both: some truth and some fiction.

It is in particular modern man who has difficulty with this, because this

‘indistinction’ or ‘unclarity’ limit his control. During my time in college, decades ago, I heard Tony Lane, then Bible teacher at London Bible College, formulate it this way in a discussion on the notion of truth with respect to the Bible: “The Bible is God’s absolute truth, told in the language of fallible man.” Theologies are a human effort and so: limited and fallible, even when they are about the unfallible God - about THE Truth. When we as mortal men want to go beyond that - as in modernism - we do not make it. We were created to humbly ackowledge God as God and to thank and honor Him accordingly. If we do not do that, when we want ‘to be as God’ ourselves and have control fully in our own hands, and there is no place anymore for wonder and awe and for acknowledging our limitations, then we go in the wrong direction (see Romans 1:17-2:1; cf. also Eccl.11:1-12:1, where the writer in almost postmodern way advocates a lifestyle of acknowledging that we do not have control fully in our own hands). Everybody who sees that, I can affirm in that acknowledgement. In the sequel of the story at Lois Shawver’s website it also appears the postmodern resistance against authority actually is resistance against glorification of the people who had ‘knowledge’ in modernism. We only need to go back half a century to arrive in a time where the Reverend or Pastor, the family Doctor and the Mayor had a status of being highly looked up to by the ‘simple workman’, because they had ‘studied’. Leanne Payne would probably cal this that the ‘workman’ in those times had been taught to be ‘bent’ towards his learned fellow creature. (By the way: authority based on knowledge isn’t a Biblical notion of authority either.) Postmodern man shakes off, one might say, this ‘bentness’, this naivety of that proverbial ‘simple workman’ from himself. The postmodern therapist likewise doesn’t want to be the ‘all-knowing’ expert anymore, like his modern colleague did; on the contrary, he wants to empower his counselee and strengthen the faith of the counselee in God and in him-/herself. And that happens more by standing as fallible man next to each other than by exclaiming as an ‘expert’ that the other is ‘seriously mentally ill’... But even that is, of course, not a matter of polarized either or. When postmodernism is going to create more balance in those things, then, as a Christian I can rejoice in that. Then I take the good - also of postmodernism - and just forget the rest of it again (cf. 1 Thessalonians 5:21). For an analysis of modern psychiatry, in which the personal aspect seemed to be lost, I also refer to: Osborne P. Wiggins & Michael Alan Schwartz, ‘The Crisis of Present-Day Psychiatry: The Loss of the Personal’, Psychiatric Times, Vol. XVI, Issue 8, August 1999. See also: Philip Troost, ‘Verwondering’ (Wonder and awe, in Dutch), Quarterly magazine Groei. |

A very clear quote on the theme of this

article, I encountered on the blog But i want easy answers!:

"The role of Job serves as paradigm for a righteous

man faced with the human condition. As often noted, Job protests against easy

answers, but the power of these protests derives from the many ways in which

Job makes his point by challenging accepted wisdom and traditional teachings.

In a very real way, Job takes on religious orthodoxy as an insufficient means

to express the complexity of life. Job protests against the reduction of

tradition into simplistic cause and effect theology."

— James D. Nogalski, “Job and Joel: Divergent Voices on a Common Theme,” in: Katharine J. Dell and Will Kynes (Eds.), Reading Job Intertextually, LHBOTS 574, T&T Clark, London, 2013, p.137.

‘A video-registration of images and poetry on Job and the visit by his friends’, text: John Piper, video: Bryan Turner, at Bryan Turner’s website. See also ‘the text of part 3. of this series of poems’, by John Piper, at John Piper’s ministry website: www.desiringGod.org.

| 2020-06-20 |

| 2008-07-26 |

Joseph Bottum, ‘Christians and Postmoderns’, First Things, February 1994.

| 2009-07-28 |

Dallas Willard, ‘What Significance Has ‘Postmodernism’ for Christian Faith?’, webdocument at his own site, not dated.

| 2010-01-29 |

Arno Gruen, ‘Reductionistic Biological Thinking and the Denial of Experience and Pain in Developmental Theories’, Journal of Humanistic Psychology, Volume 38, No. 2, Spring 1998, pp. 84-102.

| 2010-03-03 |

Kalman J. Kaplan, Matthew B. Schwartz, A Psychology

of Hope – A Biblical Response to Tragedy and Suicide, W.B.

Eerdmans, Grand Rapids MI (USA) / Cambridge (UK), 1993, 1998 (Revised &

Expanded Edn.); ISBN 978 0 8028 3271 9.

This book aptly shows a great difference between the Greek thinking and

the Jewish-Christian worldview: the root of acceptation of suicide, as a

dignified way away from the contradictions and antitheses of this life,

lies in Greek thinking, while the Judaeo-Christian world view always seeks

life.

In that, the authors draw heavily from Biblical stories and Rabbinical

literature. They also included the wonderful Rabbinical parable (p.39-40) that sharply demonstrates the failure of modernist rationalism.

It is a parable of the Eastern-European Rabbi Elchonon

Wasserman from the period between the two world wars. Facing imminent

death at the hands of the Nazi’s, this Rabbi described:

“Once a man who knew nothing at all about agriculture came to a farmer and asked to be taught about farming. The farmer took him to his field and asked him what he saw. “I see a beautiful piece of land, lush with grass, and pleasing to the eye.” Then the visitor stood aghast while the farmer plowed under the grass and turned the beautiful green field into a mass of shallow brown ditches. “Why did you ruin the field?” he demanded.

“Be patient. You will see,” said the farmer. Then the farmer showed his guest a sackful of plump kernels of wheat and said, “Tell me what you see.” The visitor described the nutritious, inviting grain – and then once more watched in shock as the farmer ruined something beautiful. This time, he walked up and down the furrows and dropped kernels into the open ground wherever he went. Then he covered the kernels with clods of soil.

“Are you insane?” the man demanded. “First you destroyed the field and then you ruined the grain!”

“Be patient. You will see.” Time went by and once more the farmer took his guest out to the field. Now they saw endless, straight rows of green stalks sprouting up from all the furrows. The visitor smiled broadly. “I apologize. Now I understand what you were doing. You made the field more beautiful than ever. The art of farming is truly marvelous.”

“No,” said the farmer. “We are not done. You must still be patient.” More time went by and the stalks were fully grown. Then the farmer came with his sickle and chopped them down as his visitor watched open-mouthed, seeing how the orderly field became an ugly scene of destruction. The farmer bound the fallen stalks into bundies and decorated the field with them. Later, he took the bundles to another area where he beat and crushed them until they became a mass of straw and loose kernels. Then he separated the kernels from the chaff and piled them up in a huge hill. Always, he told his protesting visitor, “We are not done, you must be more patient.”

Then the farmer came with his wagon and piled it high with grain which he took to a mill. There, the beautiful grain was ground into formless, choking dust. The visitor complained again. “You have taken grain and transformed it into dirt!” Again, he was told to be patient. The farmer put the dust into sacks and took it back home. He took some dust and mixed it with water while his guest marveled at the foolishness of making “whitish mud.” Then the farmer fashioned the “mud” into the shape of a loaf. The visitor saw the perfectly formed loaf and smiled broadly, but his happiness did not last. The farmer kindled a fire in an oven and put the loaf into it.

“Now I know you are insane. After all that work, you burn what you have made.”

The farmer looked at him and laughed. “Have I not told you to be patient?” Finally the farmer opened the oven and took out a freshly baked bread – crisp and brown, with an aroma that made the visitor’s mouth water.

“Come,” the farmer said. He led his guest to the kitchen table where he cut the bread and offered his now pleased visitor a liberally buttered slice. “Now,” the farmer said, “now, you understand.”

God is the Farmer and we are the fools who do not begin to understand His ways or the outcome of His plan. Only when the process is complete will we all know why all this had to be. Until then, we must be patient and have faith that everything – even when it seems destructive and painful – is part of the process that will produce goodness and beauty.

For more information, or rour reaction to the above, you can contact me via e-mail: andre.roosma@12accede.nl.

| home | or back to the articles index |